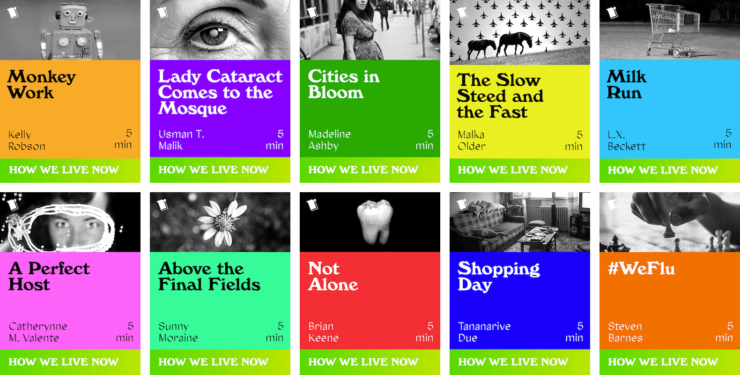

One of the debates currently taking place over various creative spheres of social media is when it’s appropriate to write stories about coronavirus—now, in the middle of it, or once we’re through it? While both sides—allowing writers and readers the necessary space to either process the pandemic or compartmentalize for their emotional well-being—are valid, Serial Box’s new short fiction collection proves that it is possible to craft engrossing fiction in this time of crisis. How We Live Now invites ten authors—Madeline Ashby, Steven Barnes, L.X. Beckett, Tananarive Due, Brian Keene, Usman T. Malik, Sunny Moraine, Malka Older, Kelly Robson, and Catherynne M. Valente—to document their feelings from the first few weeks of the coronavirus crisis through the lens of sci-fi and speculative fiction. That means quarantine and self-isolation, yes, but also zombie rats and government-mandated Blooms and sex robots.

What’s most compelling about this collection is that each story is, as Valente put it, “a snapshot of a moment.” They are individualized, highly personal responses that nonetheless manage to fulfill the aim of all great SF and spec-fic: to look ahead to possible futures (many surprisingly hopeful, all things considered) while still commenting on the present.

Best of all, the stories are all available with a free Serial Box account (sign up here or via the Serial Box app). Below, get more information on each of the ten shorts, as well as the authors sharing their various inspirations and how cathartic it was to consider the topic of “How We Live Now.”

Isolation is the Name of the Game

“Above the Final Fields” by Sunny Moraine

In extreme isolation after a global pandemic, a parent sends a message to their child.

“Writing ‘Above the Final Fields’ was a lot easier than I expected,” Sunny Moraine told Tor.com. “I wasn’t sure about my ability to approach something like this—so present and huge and raw—in such a short story, but it hit me pretty quick that it was a better idea to write around the pandemic and its social fallout rather than address it directly. So I started thinking about isolation and how we fight against that; how do you connect with someone you should know intimately and don’t? A letter presented itself almost immediately as an answer. As a form it didn’t have to be long; it actually shouldn’t be long. It was okay if the letter-writer struggled here and there with what to say, because anyone would.”

“Not Alone” by Brian Keene

At the end of the world, it’s nice not to be alone.

Not surprisingly, isolation and the struggle to connect are common themes throughout the collection: Most of the characters are stuck sheltering in place, some with younger siblings, others with undead rodents—as in Brian Keene’s story, “Not Alone,” which will resonate with fans of zombie fiction—and still more with pet parasites. Entertainment and work can only distract for so long, however, before there’s a need to venture outside, albeit as safely as possible.

“The Slow Steed and the Fast” by Malka Older

A woman and her daughter meet a stranger on the road.

“I was thinking about analogs for the experience of quarantine, so lonely travel, and the way that also can be an opportunity to experience time and the environment differently,” said Older, whose story “The Slow Steed and the Fast” projects far enough into the future where self-isolation has become a reflexive act of self-protection. “Also, I wanted to look at how habits can become ingrained into unbreakable tradition. So I wanted to look at both how this isolated time can be in some ways positive, but also how it can become a fixed practice and what misunderstandings might arise.”

The New Normal

“Milk Run” by L.X. Beckett

Running errands in a city under quarantine.

Some of the stories may hit closer to home for readers, especially those that focus on the mundanity of a pandemic. Regarding the inspiration for “Milk Run,” L.X. Beckett said, “Serial Box asked me about writing a lockdown story just as my home city, Toronto, was contemplating but not fully committed to the sheltering in place that has now, in 42 short days, become our reality. It was when everyone, if one listened to the news, was panic-buying toilet paper. Nobody knew how locked down we might be, or whether we might run out of essentials.”

“Shopping Day” by Tananarive Due

“If I’m not back by six o’clock,” Mom said, “you know what to do.”

Tananarive Due’s mind went to the same place: “I thought about shopping when I imagined the biggest challenges I face outside of the house during this pandemic. The grocery store is where I feel most exposed and unsafe, and I worry about bringing contamination into the house. With this virus, even a mild case calls for even more isolation from loved ones, with worst case scenarios where people may be separated from loved ones until they die alone. I think many of them are feeling this fear consciously and unconsciously, and I wanted to express our awareness that even our most mundane activities during a pandemic might have unthinkable consequences.”

Both Due’s “Shopping Day” and “Milk Run” employ a ticking clock to ramp up the narrators’ (and readers’) anxieties, whether it’s waiting for a mother to make it home by curfew, or an apartment complex whose residents are running out of their “essential” stashes: “My home is small,” Beckett said, “but I try as a matter of course to keep a lot of things in stock, so I was able to avoid the long lines of worried people at the grocery store. But even as I checked with a few elderly neighbours about their needs and reached out to my vulnerable loved ones about how they were doing and tried to decode all the conflicting news reports, my fears homed in on one area of great concern: securing my caffeine supply. I overbought boutique coffee beans, y’all… you would be shocked at how much well-roasted bean is stockpiled in my house. This slightly ridiculous coffee-related freakout led me to think about other functional addicts, those with state-sanctioned addictions and those whose lives are defined by prohibition. And about how we might take care of each other in this current weird situation.”

Coping and Coexisting

“Monkey Work” by Kelly Robson

On the efficacy of using sex bots to prepare biological samples for laboratory research.

Who these writers thought about in crafting their stories is especially telling: vulnerable neighbors, yes, but also the essential personnel rushing to develop vaccines in an unprecedentedly short timespan. “When I was approached about How We Live Now,” Kelly Robson said, “the pandemic lockdown had just started and everything felt so weird. I was thinking about the long hours that research scientists put in, and how so much of what they do is labor intensive. The tools they use are, by necessity, designed for human affordances, so you couldn’t just drop in a robot to take the pressure off. However, there is a class of robot that would perfect for those affordances—sex robots—and those are the same robots we are likely to have easy access to. So let’s put them to good use!” The resulting story, “Monkey Work,” is one of the standouts in the collection as much for its unorthodox solution as for the genuine warmth between scientist siblings Carlos and Jennifer. I was sorry when the story ended right at the punchline of its premise, as I would have loved to see it go further.

“A Perfect Host” by Catherynne M. Valente

She does not ride in on a white horse. She is beautiful and she is young.

Catherynne M. Valente took the even greater leap of envisioning Pestilence herself: “I wrote ‘A Perfect Host’ at the very beginning of the lockdown,” she explained. “Back when it was just barely possible, if unlikely, it might be over in 14 days, right after I skated back into the country by the skin of my teeth and figuratively boarded up my house. I wrote it quickly; it came so easily, a sketch tracing the lines of a simple image—that the corona of coronavirus was a literal crown, the one worn by Pestilence, and that Pestilence was not the rotting skeleton full of arrows of Biblical medieval art, but a modern woman well aware of all the steps we take to stop her and way ahead of the game, always longing for the Big One. At the time, I wanted to write her, in her crown, and tell people through her mouth to stay the hell home. At the time I believed they would. It was a shaky kind of optimism in March, that we would all pull together like the Blitz or something and make it out all right. Now I’m still shaky, but the optimism has headed out the back door. This story is a snapshot of a moment, a conception of the world as it was and a mind trapped inside looking up the exact flowers plague doctors stuffed up their beaks. It was strange and slightly heady to turn my feelings about the state of humanity into art so quickly. Usually I have to wait until I can process it a little. But here there was no processing, just unfiltered story, straight from the cells to the page.”

“Lady Cataract Comes to the Mosque” by Usman T. Malik

Lucid dreaming through the apocalypse.

Our brains are currently in a constant state of heightened adrenaline, and holding on to our creative impulses is more of a crapshoot than ever, so it’s no surprise that many of these stories are hyper-imaginative. As with Valente’s modern Pestilence, Usman T. Malik also places virality into a female form, this time as the blind Lady Cataract stalking the sleep of Dreamers in a cyberpunk/magical realism take on a viral infection.

“#WeFlu” by Steven Barnes

Seventeen years into quarantine, bacteria have been turned into entertainment devices. But is that really what humanity needs?

Anthropomorphizing these foreign cells was no doubt a coping mechanism for more than one writer. Steven Barnes’ “#WeFlu” imagines a future in which humans have developed symbiotic relationships with prokaryotic cells. “‘#WeFlu’ was a collision of different aspects and images: social isolation, distance working, the long-term consequences of a pandemic, and the odd fact that most of our cells are not ‘us,’” he said. “In combination, this led to several logical scenes, the notion of weaponizing prokaryotic cells, and the growing intimacy between such a demi-life form and its host. All that then remained was a crisis to bring all the important aspects to a head within 2000 words, and the story wrote itself.”

The Kids Are All Right

Many of these stories are populated with children and teenagers—no doubt processing current fears about how the youngest generations are coping with the pandemic. Lucid dreamers and latchkey kids, hedonists and travelers, these youths prove adaptive and resilient to global changes, or else grow up without ever knowing the world before—and they’re still OK, regardless.

“Cities in Bloom” by Madeline Ashby

The Bloom is a time for living inside the physical body, free from quarantine. Sometimes there are consequences.

The polyamorous teenage triad in Madeline Ashby’s “Cities in Bloom” delivers an amusing reminder that not even massive societal shifts can stop a good old-fashioned human fuck-up. Here, it’s an unplanned pregnancy during a Bloom, a government-mandated sort of reverse-Purge in which citizens are encouraged to delight in their physical bodies, consequences be damned. “‘Cities in Bloom’ was originally written as another story a while ago, for an anthology that claimed to want optimistic stories about the future,” Ashby said. “When I turned in a story about a queer poly trio of teens trying to access reproductive healthcare, the editors (and, I suspect, their corporate sponsor) said the stakes of the story ‘weren’t high enough.’ Because, as we all know, teen pregnancy is a very low-stakes endeavour. I’m happy that readers can now enjoy the story, with the benefit of editors who truly saw what it was about.”

For Malik, it was a matter of deciding what childlike innocence could be preserved, if the world were to drastically change: “I’m a slow writer in general and it can take me anywhere from a month to three months to finish a story. This one, though, was a gift from God: It simply poured out when I sat down to write. A surprisingly cathartic experience, too—even though the story goes to disturbing places. I wanted to write a story about preservation, about the salvage of innocence in inevitable, dark times. I wanted to do a summation of beauty—how phoenix-like it can be in cycles of death and rebirth. And ‘Lady Cataract’ was the story that wanted to be told; so I told it.”

Once Moraine decided on the epistolary format for their story, “I literally asked myself what I might want to say to a child I would never meet about a world they’ll never know, it flowed very quickly and felt very natural. I think I ended up with a story about connection far more than isolation, about how people find ways to reach out in the most impossible circumstances, and about how you can grieve what you’ll never get back while still finding hope in the future. Ironically it’s much more optimistic in tone than a lot of what I write. Go figure.”

How We Live Now is available now from Serial Box, free with (free) account.

Natalie Zutter marvels at how creative these writers have all managed to be. Talk SFF and speculative short fiction with her on Twitter!